|

Talk of conscription had its repercussions in our district. One young

man in a brave sounding speech declared that they would never get him. They could send all the

policemen they liked after him. But a few days later he left the homestead, and joined the armed

forces. Another young man, prominent in community affairs disappeared one night, and his body was found lying in the middle of a wheat field, an exploded revolver beside him. Reg Garrett, the youngest of four brothers enlisted in serious mood. He expressed a feeling that he would never come back. Stanley followed, as he said to "look after the kid". He was going on a temporary mission and arranged his farm affairs accordingly. One of the solemn occasions at which I officiated was the Communion Service in Bernard Hall before these two brothers and some others took their final departure for overseas. Another such occasion was a memorial service for Sapper Will Graham, killed in action. Stanley Garrett returned from the war, but Reg did not come back. Amongst my college friends to pay the supreme sacrifice were Egar, Arthur Lloyd and Starkings of Hodgeville. Casualties and bad news from the front, however, served to stiffen determination to see the grim fight through to victory. A returned man, recuperating from an operation in which a bullet was removed from his head inspired faint hearts by his eagerness to get back to the Huns. A set of lantern slides shown by a Presbyterian student showed the ruins of the Cloth Hall at Ypres, and other devastation made by the German barrage. Everything pointed to the necessity for a supreme effort including compulsory service. But by the time of its enactment there were few eligible young men left in our country to draft. Due to wet weather harvest operations were hampered and thousands of acres were still unthreshed when winter snows arrived. Progress on the church was also slow on account of the weather and labour conditions. The building was scarcely closed in when work had to be abandoned until spring. The lumber piles were buried under snowdrifts. In November I had taken out a load of wheat for Mr. Russell and brought home a load of coal and fence posts. We got the posts set, but the wire was not strung that fall. Once more I moved the cottage and stable, this time to our church property. In December I drove to Eyebrow, fifty miles, for a Confirmation Service, only to find the service had been postponed. Because we had no connection by wire, I could not be notified of the change. On the Saturday before Christmas I performed a marriage ceremony at Greenbriar and proceeded to Spring Lake for Christmas service. I stopped for the night at Walter Helm's. We decided to visit a neighbor's home and sing carols. Outside their kitchen door we started with "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing". Nothing happened for a few minutes. Then the door was opened cautiously by the man of the house. Mrs. Pearson had barricaded herself behind the kitchen table and was plainly frightened white. "Oh", she cried "I thought it was coyotes". Apparently our voices sounded anything but angelic. That was the one and only time I ever went caroling. Winter was passed in the usual manner of driving about the country, and coming home to a frozen house. I learned by the experience of a night of chills that shook my bed, that no matter how late I returned it was wise to light a fire and warm up rooms before retiring. By another exchange of horses I acquired a black colt "Cub", to drive with black "Tommy" thus making a matched team. They were a fine pair of drivers just big enough to be out of the pony class. Fitted with new rubber mounted |

harness they looked quite smart, and their performance was equal to their appearance. Driving out to Morse one day I stopped at a shack of a Russian settler. He was curious to know where I came from and what I was doing. Enlightened as to the first point he asked me about my homestead. He found it hard to believe that I was living "back there" yet held no claim. "How much you get paid for this preaching?" he questioned. "The first year I received $650; the second year $700 and this third year it will be $750." I informed him. "Ah", he remarked "It's going up all the time." On April 3rd I shoveled the snow off the church lumber, and the next day Mr. Heggie re-commenced work. There was a rush of activities in many directions, including further trips to town for lumber, visits to Spring Lake and Snake Bite, and a funeral at Maple Bush. By way of variety there was a letter to translate for Vic Fleuter. This was written in French from his homeland. Vic could not read, and had to hold the letter until someone came along to help him. This was once I was glad I had a smattering of French in School. At Snake Bite I called to see two Scottish bachelor brothers. Neither was in sight though I could hear voices down in the coulee. I waited for them to appear. It was revealed that Jock had seen me coming and had rushed down to caution Kenneth to moderate his language as he drove up the cows, for the "meenister was aboot". From this district came a family to my Sunday service at Demaine to have their children baptized. Father, mother and four children lined up across the schoolroom. The shy and struggling youngsters were held in tow by embarrassed parents while I proceeded with the ceremony. Then their little dog who would not be denied admittance eluded the doorkeeper and took his place at the end of the family line. He sat up importantly and looked into my face as if awaiting his turn to be received into the Church Militant. Any occasion no matter how painful for a trip to the city was momentous for any child in my Mission. So when Mr. Heggie's little boy was stricken with appendicitis and had to be taken to hospital, it was a day to remember. When a second boy in the family had the privilege of going out with his father to bring the invalid home, it was an unbelievable good fortune, for there was no operation in prospect to mar the trip. The child was fascinated by the sight of the railway cars and engines. When his eyes rested on a flat car on the siding he called his father's attention to it. "Look Daddy, they are going to build another car, they have the floor laid already". He had watched his father lay foundations and floor over joists of houses before erecting the superstructure. By the middle of May the church was completed and plans made to have the opening on the 27th. We had to be satisfied with homemade benches and other furniture. I was busy putting some finishing touches to the premises when I was called to the home of Harvey and Millie Cornish to baptize their little girl who was taken ill. I spent the night with the young couple. The next morning the baby died. Returning home I fed my team and set out for Riverhurst to meet Rural Dean Blodgett who was coming for the church opening. There was a high wind prevailing and the ferry could not operate. I sat all day on the river bank waiting for the wind to fall. In the evening I crossed the stream and at dark reached town. There I could find no trace of my passenger. He had not arrived. There was nothing to do but return home through the night, the ferry as usual, being lighted by the feeble glow of a lantern. The next day, Saturday, I drove to Demaine again and |

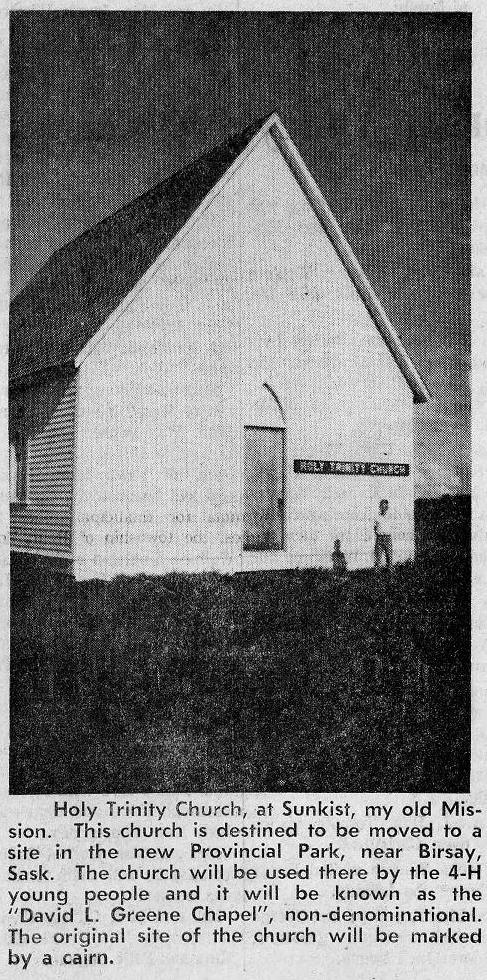

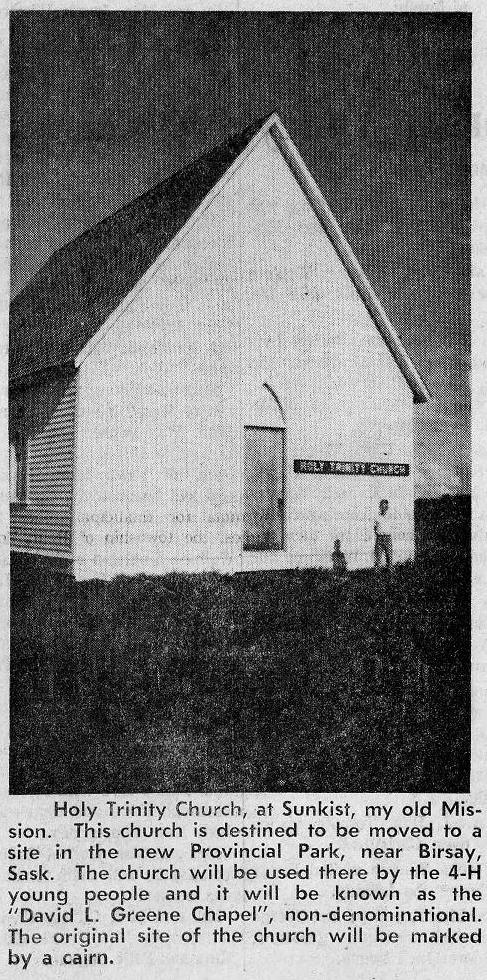

conducted the funeral service of baby Cornish. East of our church at Sunkist a new municipal

cemetery had been surveyed and fenced. Like the tomb of Joseph of Arimithea prior to the Crucifixion

it was a burial place "Wherein was never yet man laid". Here we committed to mother earth

the baby of Harvey's and Millie's first-born. Thus was a little child to lead to their last resting

place the ever lengthening procession of Canaan's blessed dead. On our return from the cemetery I beheld an unusual sight of an automobile standing beside the church. My brother had decided at the last moment to motor Mr. Blogett to the church opening. Our parents and my brother's wife had also come. This was indeed a pleasant surprise and quite made up for my fruitless trip to Riverhurst. On Sunday, May 27, 1917, the only church of any denomination within a radius of 40 miles was dedicated at Sunkist. It was a triumphant occasion. By long and patient effort the pioneer people had emulated Abraham by setting up an altar in their chosen land as I had suggested to them 7 years before. In deference to my association with them in the work they called the church "Trinity" after the old stone church at Oak Leaf, Ontario where I was baptized. At the close of a most impressive service Rural Dean Blodgett called a meeting of parishioners. At this gathering he made the disconcerting announcement that he was planning for my removal to a small town parish. This was unwelcome news, and it brought forth protests. Mrs. Rusnell voiced a common feeling when she said "But Mr. Greene belongs to us". (Author's note. In July 1949 I motored from Duck Lake, Sask. To Lucky Lake, and conducted the funeral service of Mrs. Rusnell). Personally I did not want to in the least leave these people, and I became reconciled to the idea only when I was assured that another ordained clergyman, and not a summer student be sent to the field. I was the only minister of the gospel resident in an area comprising several townships, and I felt the need of these scattered people was far greater than that of town residents, who had access to several churches. But Mr. Blodgett insisted that I had been living under conditions of isolation long enough, and that I must have a change. A patient is considered incompetent to judge of his own physical and mental condition, and for all I know I might have been getting "prairie wooled" a term comparable to "busted" as understood in the timber country. Anyhow it was decreed that I should move to Elbow in a month's time. My remaining weeks were filled with hectic days and nights of farewell visits and social functions, for I tried to see everyone in that extensive territory. I sold some of my belongings, and hauled the balance out to Elbow in Sutton's democrat. My handsome team of black drivers wearing rubber mounted harness became passe. I was loathe to part with my equine friends that had hauled me over thousands of miles of muddy trails in summer, and through snow drifts in winter to the tune of tinkling sleigh bells. But it was no use protesting against the march of progress. I shall never forget the habits of those two beasts. Cub, the younger of the pair, used to break suddenly into a furious gallop for no reason except to gratify an urge for speed. In the stable Tommy used to eye my movements in his mate's stall and turning his head flatwise take a nip at my shirt, frequently biting too deep, and pinching the flesh. When I gave him a slap on his long horse face he would blink an apologetic eye as if to say "Sorry, boss. I did not mean to hurt you". Those two beasts were playboys at heart, yet they willingly racked up the miles at a comfortable nine miles per hour pace. I sold the pair to a bachelor homesteader on time. |

|